Charity begins at home, it is said.

African leaders have become increasingly vocal on global crises, often rushing to invoke international law, the United Nations, and multilateral institutions whenever violations occur far from the continent.

To directly receive articles from Tendai Ruben Mbofana, please join his WhatsApp Channel on: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaqprWCIyPtRnKpkHe08

In principle, there is nothing wrong with this.

In fact, it is commendable.

International law exists precisely to restrain the excesses of power, protect sovereignty, and safeguard human dignity.

When these principles are violated—whether in Palestine, Venezuela, or anywhere else—the international community has a duty to speak out.

However, what has become impossible to ignore is the glaring hypocrisy and double standards displayed by some African leaders, who find their voices only when injustice is geographically convenient, while maintaining a deafening silence when the same international laws are violated right here on African soil.

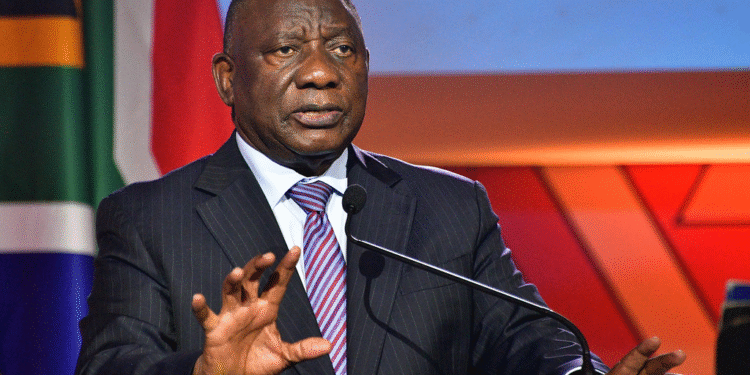

The recent call by South African President Cyril Ramaphosa for an urgent United Nations Security Council meeting following yesterday’s US military action in Venezuela is a case in point.

According to South Africa’s own Department of International Relations and Cooperation, the operation constituted a “manifest violation” of the United Nations Charter.

On this, Pretoria is correct.

Article 2(4) of the UN Charter explicitly prohibits the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.

Article 2(7) further bars external intervention in matters essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of sovereign nations.

The capture and removal of Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro by a foreign power is a textbook case of unlawful intervention.

No defender of international law should object to South Africa raising the alarm.

But principles, if they are to mean anything, must be applied consistently.

This is where President Ramaphosa’s moral authority begins to unravel.

Barely a month after Zimbabwe’s deeply flawed 2023 harmonised elections, the Southern African Development Community Election Observer Mission itself declared that the polls had “fallen short of the requirements of the Constitution of Zimbabwe, the Electoral Act and the SADC Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections.”

These are not opposition claims.

They are findings from a regional body to which South Africa is a leading member.

The violations cited included the lack of transparency, an uneven playing field, intimidation, the abuse of state resources, media bias, and serious concerns over the independence of the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission.

These are direct breaches of SADC’s own democratic norms.

What was President Ramaphosa’s response?

Silence.

When an extraordinary SADC Heads of State and Government Summit was convened in Luanda in November 2023, Zimbabwe’s electoral crisis was conspicuously avoided.

No call for accountability.

No demand for reforms.

No insistence that a member state respect the very rules it had signed up to.

The summit proceeded as if nothing was wrong, save for issuing statements on the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Yet only weeks later, Ramaphosa was before the International Court of Justice, accusing Israel of genocide in Gaza—a move many applauded, and rightly so, given the catastrophic humanitarian toll on Palestinians.

This selective urgency raises an uncomfortable question: are violations of international law only worth confronting when they involve non-African states?

Zimbabwe’s crisis is not limited to flawed elections.

For decades, the ZANU-PF regime has presided over widespread repression that squarely violates international law.

Arbitrary arrests, torture, enforced disappearances, the violent suppression of protests, and the systematic denial of political freedoms breach the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Zimbabwe is a party.

The killing of unarmed protesters by state security forces in August 2018 and January 2019 constituted violations of the right to life under Article 6 of the ICCPR and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

These events occurred while Ramaphosa was already President of South Africa.

Once again, his response was silence.

Yet when Ramaphosa justifies taking Israel to the ICJ or calling for urgent UN action on Venezuela, he invokes concern for the welfare and wellbeing of civilians, the sanctity of international law, and the dangers of impunity.

If that concern is genuine, then one must ask: does it not extend to Zimbabweans?

Are they less deserving of solidarity because their oppressor wears the badge of a liberation movement?

Do Palestinians and Venezuelans matter more than fellow Africans living just across South Africa’s northern border?

This hypocrisy is not new.

In 2008, under President Thabo Mbeki, South Africa infamously declared that there was “no crisis in Zimbabwe” at the very moment when the Mugabe regime was unleashing one of the most brutal campaigns of political violence in the country’s history—killing hundreds and mutilating thousands after losing the first round of elections to Morgan Tsvangirai.

Yet in December 2025, the same Mbeki publicly declared that there was a crisis in relatively peaceful and democratic South Africa.

The irony is staggering.

This is the enduring tragedy of South Africa’s foreign policy posture.

It desperately wants to be seen as a global moral voice—leveraging its membership in BRICS, the G20, and its liberation legacy—while failing, often deliberately, to confront injustice in its own neighbourhood.

In Shona, we call this ushewokunze: the tendency to perform for outsiders while neglecting responsibilities at home.

Charity, as the saying goes, begins at home.

There is nothing wrong with South Africa confronting powerful states like the US or Israel when they violate international law.

In fact, that courage is admirable.

But moral credibility is built through consistency, not spectacle.

You cannot claim to defend a rules-based international order while ignoring the routine abuse of those same rules by your closest allies.

You cannot posture as Africa’s conscience while abandoning Africans whose voices are silenced by repression.

If South Africa, the continent’s most influential state, refuses to speak for Zimbabweans, then who will?

Who gives voice to the citizens of a small, economically broken country when their suffering is inconvenient to regional power politics?

President Ramaphosa may aspire to global relevance, but true leadership is first tested at home.

Until South Africa finds the courage to confront injustice in its own backyard with the same urgency it displays on distant shores, its moral sermons at the United Nations will ring hollow.