Zimbabwe has become a hunting ground for crooks, many of whom now prowl online looking for their next victim.

When we purchase goods or services in Zimbabwe, we do so in good faith — trusting that what is advertised is truly what we are paying for.

To directly receive articles from Tendai Ruben Mbofana, please join his WhatsApp Channel on: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaqprWCIyPtRnKpkHe08

That basic expectation of honesty should be the foundation of every business transaction.

Yet, far too often, consumers are deceived by unscrupulous companies that exploit this trust, leaving people feeling helpless, frustrated, and financially betrayed.

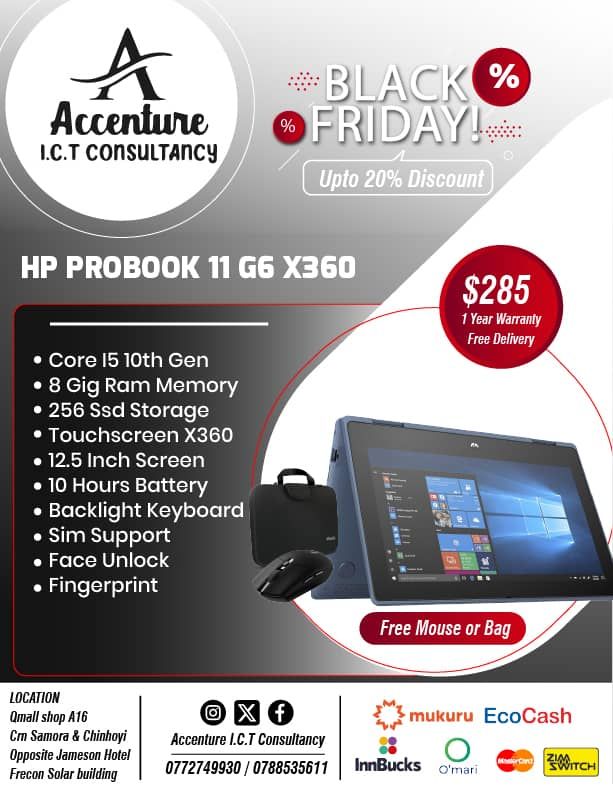

I recently found myself in exactly that position after purchasing what was advertised as an HP ProBook 11 G6 x360 laptop from a company called Accenture I.C.T Consultancy, based at QMall in Harare.

Their advertisement proudly listed several features, including one particularly important to my professional work: a backlit keyboard.

As someone who writes extensively on social justice issues — often late into the night during Zimbabwe’s prolonged power outages — this was essential.

After years of struggling with a laptop without a keyboard backlight, seeing this model advertised felt like the ideal and affordable solution.

I paid US$285 — a significant amount for any ordinary Zimbabwean — and looked forward to finally having a device that met my needs.

The excitement ended the moment I received the laptop on 13 November 2025.

The keyboard had no backlight, no function keys for lighting, and no possibility of activating a feature that simply did not exist.

It was immediate and undeniable: I had been misled.

The company had explicitly advertised a feature that was not present in the product they sold.

This is a clear example of false advertising, directly violating Section 10(2)(b) of the Consumer Protection Act [Chapter 14:44], which prohibits businesses from inducing consumers through misleading representations.

I immediately wrote to Accenture I.C.T Consultancy demanding redress — either a replacement with the correct model as advertised or a full refund.

Instead of treating the complaint with the seriousness it deserved, the company initially ignored the message entirely.

There was no acknowledgement, no apology, and no attempt to correct the issue.

When the silence persisted, I escalated the matter by lodging formal complaints with the Consumer Protection Commission and the Consumer Council of Zimbabwe, attaching my correspondence with the company, the advert, and the receipt.

I also informed my legal representatives, preparing to pursue further action should the company continue refusing to resolve the matter.

Interestingly, it was only after these escalations that the company finally contacted me on Friday, 14 November 2025.

They assured me the laptop would be replaced on Monday, 17 November.

But on Monday morning, the story changed.

They claimed the replacement unit had not yet arrived from South Africa, though they insisted it was expected that day.

Later that evening, they contacted me again, saying the replacement laptop had arrived and would definitely be dispatched the following day.

The next morning they assured me once more that the laptop was now being prepared for dispatch to Kwekwe.

Then, without warning, everything changed.

All their communication lines — both phone numbers and WhatsApp — suddenly became unavailable.

Calls would not go through.

Messages would not deliver.

Every attempt to obtain an update was met with silence.

It was only after this sudden disappearance that I finally managed to get hold of them again.

They once more promised to send the replacement laptop “the following day” — which is today — but they have failed to do so.

They have not responded to a single one of my follow-up inquiries.

This pattern of shifting stories, empty promises, and sudden communication breakdowns raises serious questions about consumer protection and business ethics in Zimbabwe.

It is not only about a backlit keyboard.

It is about trust, accountability, and the treatment of ordinary citizens who simply expect to receive what they paid for.

For most people, US$285 is not spare change.

It represents months of sacrifice and careful budgeting.

To have that hard-earned money taken through false advertising is not just unfair — it is immoral.

The Consumer Protection Act exists for a reason: to prevent exactly this kind of misconduct.

But laws mean little if not enforced.

When companies can blatantly misrepresent products, ignore complaints, issue hollow promises, and then vanish the moment accountability is required, it becomes clear that enforcement mechanisms are either weak or being ignored entirely.

The result is a marketplace where deceit feels easier than honesty — and the burden of justice falls entirely on the consumer.

My intention in sharing this story is not merely to highlight my own frustration, but to warn others and urge the authorities to act.

Too many Zimbabweans are falling victim to similar schemes because dishonest businesses know they can get away with it.

If consumers remain silent, the pattern will continue.

If authorities fail to intervene, unscrupulous traders will keep preying on trusting citizens who simply want to receive what they paid for.

As things stand, I remain uncertain whether the promised replacement will ever be delivered.

Their repeated broken promises — followed by silence — speak for themselves.

What I do know is that I will pursue this matter to its conclusion, not only for my own sake but to ensure such behaviour does not go unchallenged.

Zimbabweans deserve better than a marketplace where deception thrives unchecked.

Trust is not a luxury in business; it is a basic obligation.

And those who violate it must be held accountable.